SHOYO'S THEORIES

This section includes translations of three more of Shoyo’s essays. The landmark 'Preface to a commentary on Macbeth' expounds Shoyo's theory of Shakespeare in the context of 'the hidden ideals' debate (botsuriso ronso) with the writer Mori Ogai in the early 1890s. 'The bottomless lake' (published in the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper on 1st January, 1891) also contributed to that debate, and serves as an imagi native variation on his literary theories. Shoyo's anti-elitism is also evident in his lengthy Theory of Musical Drama

(1904) of which the first part is translated below. Some sentences have also been omitted from the other sentences.

① ‘Preface to a commentary on Macbeth’ (Waseda Bungaku, October 1891)

Among the plays ascribed to Shakespeare’s authorship no more than about thirty-six can be said to have been written definitely by Shakespeare himself, and these were written between the years 1588 (when the writer was 24) and 1613. […] There are four main periods in his career according to the development of his technique, dramatic structures and ideas. The first period comprises his formative years, the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet

and a number of what we might call light-hearted satirical comedies. The second period gives us his more spirited comedies and the history plays, the third his profound tragedies and tragicomedies (cheerful on the surface and pitiless underneath), while the fourth is one of quiet dignity, characterized by a graceful and animating blend of tragic and comic elements. It goes without saying that the relative merits of Shakespeare’s ideas, technique and dramaturgy vary from period to period, which is why anyone approaching Shakespeare for the first time should read one or two works from each of the four periods.

Adopting a methodical approach, we should start with the plays of the third period as preliminary to a discussion of the first and second. This is because the earlier plays use more euphonious effects and colloquial language which demand more explanation for people who do not know English. It is my intention that the commentary I provide here might be of assistance to such people. The history plays of the second period – not the comedies – can be of only limited interest to those unfamiliar with English history, requiring tedious explanatory notes besides being dramatically inferior to those of the third. In other words, since the main purpose of this commentary is to make the body of Shakespeare’s works more widely known among Japanese people, it is only natural that their initial experience should be of Shakespeare at his most sublime, which is why I focus on Macbeth, the greatest of his four tragedies.

There are those who argue that in order to achieve my purpose some kind of literal translation is preferable to tedious notes, although this is not something I can do with any degree of literary merit. For this reason, I mainly follow the diction of the original, explaining the sense and always trying to convey its poetic beauty. Readers unaware of the beauty of Shakespeare’s English should of course turn to the original, leaving me only to clarify some of the expressions.

There are two principles to an effective commentary. The first relates to the rhetoric, and is to comment on the meaning of words, grammar and so on as they appear in the source. This is critical commentary, expounding the author’s intentions and ideas as they are revealed in the original texts. When I set about my commentary on Macbeth

I thought that I would be adopting solely the second type of commentary, but on reflection decided that the first type was preferable. The second type – that of interpretation – can be an extremely profound and profitable method for the more perceptive readers, but for the less perceptive a little learning can be a dangerous thing, and for the inattentive can lead to undesirable errors. These tendencies are born no doubt from the remarkable resemblance of Shakespeare’s works to nature itself: a thesis in itself that I will develop a little in this essay.

To claim that the plays of Shakespeare resemble nature is not to suggest that the characters and situations are actually real. Shakespeare’s plays exist in the hearts of readers, whose mysteries the plays enable readers to interpret; they treat on what is natural about the human endeavour. Looking objectively at the human heart, human nature is seen to incline naturally toward both the good and bad: the cantankerous old stepdame and the affectionate mother. Bitter and disappointed people will resent Shakespeare’s creativity; they are such people who spurn nature and revile this suffering world. Talented people will oppose that attitude, regarding Shakespeare’s creativity as like the affectionate mother and this world a garden of delights. Yet, whatever people’s feelings on the matter, it is their experience of suffering and joy that constitute the two poles of our nature. One must first analyze his views on fate and then his Christian beliefs.

Western and Oriental traditions each have their own ways of looking at creativity, for creativity is greater than all the manifold perspectives of West and East: boundless indeed as the doctrine of ‘consciousness only’ taught by the Hosso sect (1). The Lord Buddha tells us that the sound of the gong of the Jetavana monastery resounds with the echoes of nirvana but in the twilight hour lovers hear nothing (2). The pessimist cannot perceive the truth of impermanence in the rapid blooming of the sala

flowers, while the young maiden who has never known sadness has not seen anything. No human being can know the goal of creativity, but we can at least greet the sadness of autumn with a melancholy heart and the birds and flowers of the spring with a glad one.

Creativity fulfils itself in an empty heart. Shakespeare’s plays are very close to this meaning of creativity. Scholars, whether they happen to be of refined aesthetic knowledge or more superficial in their outlook, reserve for Shakespeare a blind praise and adoration inspired by the sages of old. Shakespeare’s works are magnanimous, gratifying all tastes; they are as desirable to the ordinary man as the beauties of nature. The works of writers such as Byron and Swift, enjoyed by some and despised by others, are altogether different, a matter of mere personal taste, whereas Shakespeare’s works may be likened to ‘the face that launched a thousand ships’, that is to say to the essence of creativity.

From the previous generation of Japanese Shakespeareans there have come a hundred or so books and articles, some critical and others more interpretive, and in extreme cases, for example with regard to the character of Hamlet, the critics have been in complete disagreement. Just as it is difficult to define creativity, so too is there no fixed, unchanging Shakespeare, but whatever one’s shade of opinion any interpretation of Shakespeare must have its own rationale. With this in mind, there have been few critics since Johnson and Coleridge who have failed to mention the word ‘nature’ when writing on Shakespeare. I used the metaphor of a bottomless lake in a recent study on drama, and an essay by Dowden compares Shakespeare and Goethe to a great ocean (3). Although our intentions may have been rather different, I believe they were both founded on the same basic principle.

As Carlyle observed (4), Shakespeare was originally a stage hand at the Globe Theatre before turning to writing, and it was as a stage hand that he learned to become a poet of nature, no different from any popular writer of the real world, which is to say that in learning to win over the hearts of his audience he acquired an esoteric knowledge of human nature that is not dissimilar to his dramatic portrayals. He observes human beings in the fullness of his poetic understanding, and in his fair and impartial style is able to portray human nature as it is without actually flattering his audience.

I would like to suggest that Shakespeare is our own Chikamatsu Monzaemon writ large. There is no fundamental difference between the glittering jewel of true teaching and that of approbation, for if there were so then human behaviour would be without motive. Shakespeare’s is the very jewel of nature; it is able to liberate nature’s spirit, to stir the rustics, the maidens and Benka of old (5) from their apathy, but though we may price his jewel as highly as a castle, it is in itself no more than a rare stone, worth no more than any passing fad, for it is only human nature to inflate the value of the things we admire.

The works of Shakespeare are like a mirror reflecting the faces, that is to say ideals of all their many hundreds of readers. Gervinus found his philosophy in Shakespeare’s works, as did Bräker, Bucknill, Moulton, Hudson and Dowden in more recent times (6); they all have been stunned in the realization that it is Shakespeare alone who is without ideals. There has never been as great a poet as Shakespeare, neither before nor since. No one approaches Shakespeare’s creativity, which is as broad and deep as the ocean itself, or a bottomless lake. It is remarkable how many readers have found their own ideals reflected in Shakespeare’s works, and surely this is because they never seem to manifest any single big idea. Despite some private reservations, I have generally been in agreement with the critical consensus that Chikamatsu’s domestic sewamono, plays such as Ten no Amijima, Abura jigoku, Koi no tayori

and Date some tazuna, all of them embrace ‘small ideals’ (7). The theme of Ten no Amijima, as I noted in a study published this year, may be compared with Romeo and Juliet as being like that of a younger brother to his elder brother, and our beloved Abura no jigoku

accounted even more profound than The Tempest.

Of course that is just the ideas, and as dramatic works of art the two writers are hardly similar. If Chikamatsu had been born in the Elizabethan age, writing his sewamono

in English to be edited by Rowe, construed and extolled by Johnson and Pope, criticized and appraised by Coleridge and Hazlitt, and annotated by Malone and Warburton, who would have formed an academic society for the study of Chikamatsu, before being catalogued by Abbott and Schmidt and brought to a yet wider public in Europe and America by the likes of Goethe and Lessing, if in other words he had approached Shakespeare’s reputation, then we can suppose that he would have amounted to something rather more than a mere writer of Japanese puppet plays, and this is because, as with Shakespeare, of his plays’ remarkable capacity to portray nature as it is.

This is not to disparage Shakespeare by insinuating that he is no match for the puppet theatre, and nor is it to say his works are no more than some ordinary gemstone. There is no denying his uncommon brilliance, but since his works can only be evaluated as such within the hearts of readers, it is foolish to judge them according to the teachings of the ancients. If we are to appreciate Shakespeare, it is natural to praise his art for animating the feelings of human beings and for the unprecedented singularity of his creativity, his figures of speech and his other devices, and yet as far as his ideas are concerned he cannot be regarded as some great philosopher. Rather, we can praise him only for his hidden ideals.

One cannot make something out of nothing. The Zen and other classics of old may have been praised as works of great ideals when in fact their ideals are hidden, and much the same may be said of works of small ideals. The desires of an infant can be said to conceal both evil cravings and a healthy appetite. The sentiments of Onitsura’s haiku, ‘Autumn has come. My unfeeling heart.’ (8), are to be found hidden in the many strands of Eastern and Western philosophical thought just as much as they are in Buddhism. In the pen of the great Macaulay, the momentary heroism of Kiuchi Sogo would bear comparison with a Hampden or Washington (9), and in the poems of Onitsura and the other haikuists, Kiuchi and the others require no footnotes. The infant who knows no language requires only that its interpreters listen with a sympathetic heart.

I suppose that if Shakespeare had written his tragedies in prose, as novels, they would have been of lesser value, which is because it would have been harder for them to conceal their ideals. The tragedy of King Lear, for example, would be seen to have the same moralistic purpose as a Bakin novel, because Shakespeare never gives his own opinion in the play, and so its meaning can be deduced only from the surface details of the plot: interpret it as one will. To give an example from one of Bakin’s novels, the characters of Mr and Mrs Hikiroku are depicted with great vigour and realism, but from the viewpoint of hidden ideals the story has a clear moralistic purpose (10). The author is clearly visible within the story. Likewise, Basho’s famous ‘frog’ sonnet has various interpretations but they all stem from the same author’s point of view, and so too The Tale of Genji.

Although the proof for my argument is still undeveloped, I can just about understand why it is that hidden ideals are not necessarily great ideals, and small ideals can sometimes appear as hidden. In any case, I am convinced of the futility of imposing ideals on those great works in which they are artfully hidden, and so this commentary on Macbeth

seeks mainly to clarify the superficial meanings of the text and not enlarge my own ‘ideas’. Nevertheless, where differing interpretations may be thought possible, I have as much as possible stated my own opinion rather than those of previous commentators. As for a more complete interpretation, the individual reader must provide that himself. Those with a Japanese way of thinking will find Japan in the play of Macbeth. Those with a universal way of thinking will find the world, and those with their eyes on eternity will find eternity. The poem of hidden ideals is as exhaustibly fascinating as the great and magnanimous ocean itself.

‘‘Makubesu hyoshaku’ no shogen’, in Shoyo Kyokai, ed., Shoyo senshū, Add. Vol. 3, Tokyo: Daiichi Shobo, 1978, pp. 161–9.

Notes

1. The Hosso school of Buddhism, which was introduced into Japan in the 7th century, teaches that all phenomena are phenomena of the mind.

2. The reference is to the opening of The Tale of Heike

(completed before 1330): ‘The sound of the Gion Shoja temple bells echoes the impermanence of all things; the color of the sala

flowers reveals the truth that to flourish is to fall. The proud do not endure, like a passing dream on a night in spring; the mighty fall at last, to be no more than dust before the wind.’ (trans. Helen McCullough, 1988) Gion is the Japanese name for the Jetavana monastery in northern India, where the Buddha preached frequently, and of a temple in Kyoto where the story begins. The briefly flowering sala

trees symbolize impermanence in Buddhism, and the tolls of temple bells the alternate states of nirvana and impermanence, which for Tsubouchi is a Shakespearean image of the whole of human life contained within a moment in time.

3. For Tsubouchi, Shakespeare’s genius is represented by the sea – or lake – itself, while Dowden likens Shakespeare to a mariner who since ‘he had sent down his plummet farther into the depths than other men, […] knew better than others how fathomless for human thought those depths remain.’ (Edward Dowden, Shakspere: A Critical Study of His Mind and Art, 1875, p. 35)

4. Historian Thomas Carlyle popularized the notion of Shakespeare as ‘poet as hero’ in his influential On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Hero in History

(1841).

5. According to the legend, Benka lived in the 9th century kingdom of Chu in southern China, and had his left foot cut off when the king refused to believe that a valuable gem he had found in the mountains was real. When he presented a mere stone to the king’s successor, he had his right foot cut off, but when he polished the stone so that it became a gem and presented it to this king’s successor, its worth was finally recognized, and later sold in exchange for fifteen castles.

6. Prominent Shakespeareans familiar to Tsubouchi: Georg Gottfried Gervinus (1805-71), German literary historian who wrote a commentary on Shakespeare; Ulrich Bräker (1735-98), Swiss autodidact who wrote commentaries on each of Shakespeare’s plays; Sir John Bucknill (1817-97), eminent psychiatrist who wrote on Shakespeare’s medical knowledge; Richard Green Moulton (1849-1924), American academic whose analytical approach to Shakespeare strongly influenced Tsubouchi; Henry Norman Hudson (1814-86), American scholar whose Shakespeare criticism was read by Emily Dickinson; and, lastly, the Irish critic and poet Edward Dowden (1843-1913).

7. Sewamono

(‘domestic tragedies’) originally written by Chikamatsu for the joruri

puppet theatre (and later adapted for the kabuki): Shinju ten no Amijima

(The Love Suicides at Amijima, 1720), Onnagoroshi abura no jigoku

(The Woman-Killer and the Hell of Oil, 1721), Meido no hikyaku

(The Courier for Hell, 1711, which Tsubouchi apparently confuses with a later play by another playwright with the same plot, Koi no tayori Yamato orai), and the last probably referring to Tamba Yosaku no machiyo no komurobushi

(The Night Song of Yosaku from Tanba, 1707).

8. Renowned haiku poet Uejima Onitsura (1661-1738). The original Japanese reads Nande aki no kita tomo miezu kokoro kara.

9. Affectionately known as Sogo-sama (1605-53), Sakura (Kiuchi) Sogoro was crucified together with his sons after appealing to the shogun above the head of his local lord against the heavy taxes his villagers were having to pay despite poor crops. No historical evidence has been found for the incident, so he may be only a legendary martyr. The works of the Whig historian Lord Macaulay (1800-59), who praised parliamentarian John Hampden (c. 1595-1643) as the originator of the English Revolution for his refusal to pay Charles I’s ship tax in 1637, would have been known to Tsubouchi from his study of English history at the Imperial University.

10. Takizawa (or Kyokutei) Bakin (1767-1848), the best known of fiction writers from the late Edo era, whom Tsubouchi read as a child and later criticized in Shosetsu shinzui

(The Essence of the Novel, 1885) for his didacticism and lack of psychological depth. Mr and Mrs Hikiroku appear in Bakin’s epic novel Nanso satomi hakkenden

(The Eight Dog Chronicles, 1814-42).

② ‘The Bottomless Lake’ (Yomiuri Shimbun, 1st January, 1891)

Last night I had a mysterious dream. It was of a place I knew not: a lake perhaps, a pond or a marsh, no more than a hundred yards in circumference … or was it half a mile round or ten times that length? At any rate, it was the shape of a hen’s egg, having neither beginning nor end, and the mountains around it seemed to weather all four seasons at once, the scent of cherry blossom, peach and apricot vying with the red leaves of autumn. Peaks towered into the sky above. The water of eight thousand generations whirled into the abode of dragons beneath (1). Creaks and waterfalls reverberated with a sound like thunder. The hollows were shrouded in dense mist, and though they seemed narrow places of little depth extended many thousands of leagues into the earth, and were quite impenetrable.

A warm spring breeze rustled the tender branches of the willow trees as though caressing the hair of a fair maiden, and turned the blossoms to crimson like the lips of an innocent girl. Here a white crane alighted on the plum tree, and the spirit of a great warrior passed beneath its moonlit branches. Here too could be seen the withered pampas of winter and a perilous log bridge, a place where ascetics smilingly brush off the cares of this world with the sleeve of the ten virtues (2): a place for laughter babbling like the mountain brooks, a place for weeping at the sadness of things, the Pure Land (3), golden flowers and leaves reflected in the water, sands beneath the water, the trees of summer and fruits of autumn, casting their fiery glances through the foliage. All merged indefinably into each other in this heavenly pleasure garden filled with gold-plumed singing birds, celestial flowers of a hundred different colours dancing like the gods. Below that stood a hermit’s hut with its spiritual splendours, a stream bearing the fading leaves of autumn in its train like a lone cloud, the heart of man in the cycle of nature. As the wind eased, the sensual figure of a beautiful woman emerged naked from her toilette of vernal rain and peonies. Such a changeable world of spirits this was, one aspect opening on to a hundred others and ten thousand more, spring to autumn, autumn to summer, summer winter. What a marvellous thing it is when laughter turns into anger, sadness joy, vulgarity refinement, the rough into the smooth.

Yonder stood a tall post that had been exposed to rain and dew for many a year, and on it could be traced these words: ‘The bottomless pond, landmark of the literary world.’ Whether this notice was erected many years ago by some functionary I did not know, and I stopped and stood in amazement. Dressed in clothes that might have been from any time or place appeared a man from I knew not where. He waved a fan in his right hand and in his left hand held a thick stick, which he tapped, and called out to two others behind him, a father and son. The one was a follower of Confucius, and the other a Christian. Presently the three became one, and standing by the roots of a pine tree, they admired the scene. Father and son lifted their hands in wonder, bathed in sunlight by this remarkable lake. The waves lapped softly, water fowl floated in harmony together, male and female dutifully at one, a crow perched on its withered branch (4), all was as it should have been. This was a bewitching lake indeed, with its sapient mountains and benevolent plum trees. Gnarled pine and oak trees weathered the snows and frosts, and beyond wove the willow trees. A single tree bespoke the virtues of moderation and discretion, while scattering maples revealed the essence of the ancient virtues, those which the heart has always treasured. Like the constant prayers of a monk on his way, the fall of the maple leaves told the emptiness of earthly existence. The sight of placid waters was an illusion; the abundant trees without number were comparable to the 84,000 cycles of reincarnation (5). Here there blossomed fruits of cherry, peach and apricot, their fruits ripening in the sun.

Never had there been such a garden, this place illuminated by the true light of the law of cause and effect, growth and decay, where no evil enters in; it was like the Sea of Bokkai or the third realm in the Buddhist law (6). Looking at the foaming waters, I could see for myself the nothingness at the heart of all living things. The Christian assuaged my anguish at this floating world, pointing to the fruits that ripened as the blossom fell; his hope for eternity could be seen in the spring buds that succeed to the leaves of autumn just as the flowing waters of the lake intimated the limitless blue expanse of the sea. The lake was a microcosm of earthly life, the sea a boundless heaven. The Christian cried out in his dread ‘O Lord!’, for the way to hell passes also to the gate of heaven. This exquisite lake of the gods I intently admired was so shallow you could walk across it. Father, son and pilgrim sat together with their legs over a precipice deeper than one could have possibly imagined. One step after another they made their way together down the cliff into the dark and cruel abyss.

The place they descended was precipitous. They wore quaint old caps and gorgeously crested robes. They held compasses in the palms of their hands, and – like Benkei of old – on their backs carried the seven tools and cloths for polishing metal (7). Checking their watches, they looked back and forth. One looked to be a philosopher, skilled in knowing the difference between self and other. Before him stretched the beautiful lake with its undulating mountains; behind him on the cliff arranged in a tidy row like the forty-seven symbols of the Japanese syllabary lowered terrifying boulders like snarling tigers. […] The flowers of spring emitted lovely sounds, and gathered them in again in a single place beneath the gaze of autumn. There is no greater diversity within unity, nothing rarer nor more extraordinary: how true and auspicious this vision of water and flowers in the mountains. The water gushed forth like jewels from waterfalls to the creeks and shoals beneath, changing like the snow. Leaves lay scattered recklessly about, their unsightliness vanishing with the slightest touch of white water, and beneath the crimson maples ambled deer, and the wild boar seeking shade among the bush clover. So too might a troubled heart have found repose among the bamboo.

Presently, there appeared someone from behind a tree: an old man white-browed and brimming with knowledge, who could read ten or more lines at a glance. Wearing a robe of Chinese vermillion and a splendid crown, he held a wooden scepter in his right hand, and in his left a wand, and stood with one foot on the sand, the other on the leaves, white against black. Wanting to know this person better I come close: he seemed to me like the lake itself, its master indeed. The pine trees before him were truly the ancestors of Takasago (8). The wild cherry trees looked as if they had somehow been transported from the southern side of Nyoirindo Hall (9). The mountains to the west of the lake shone brightly, and I gazed enraptured at their shadows. Luminous grasses sprang from a single plant; the place was without weeds. I felt as if they too had been transplanted from the renowned Maple Bridge outside the castle walls (10).

Along this lonely lake one evening came the great sage, who had but one sorrow. For as the hour turned to four, his mind was suddenly disturbed. Here autumn was no different from summer or winter, even if there happened to be no red leaves in the spring, and in the autumn cherry did not blossom. The confusion of seasons meant that time stood still in the hermit’s hut, this lonely retreat where the heart knew no evil. The sage […] stood above me, nodding at my words. I heard the inflections in his voice, wondrous to my ears. The white-browed scholar advanced unsteadily on his stick. Taking three steps, he faltered now and uttered a cry; the people behind him gasped in astonishment. There were sprites in the water, sprites too in the hermit’s dwelling: fearful creatures from which one kept one’s distance, tongues rolling in their heads, legs hollow, bodies deformed, they hid in the undergrowth.

[…]

A young man looked up from the shadows of the trees, smiled at what he saw, and walked slowly along the shore. He wore an embellished cap of such beauty that it would have outshone nature itself, and his clothes and shoes were of amazing artistry and beauty as well. He opened his mouth sweetly. Nothing is comparable to the exquisite beauty of nature. No words are fit to praise it, and it would be foolish to try. If you wish to know the purpose of this pretty satire, just consider the simple idea at its heart, the magnificence of its structure, the limitless beauty of even just one portion of the learning contained herein, and abandon your prejudices and lies, your madness and your folly. Only the subtle majesty of a new dawn is worthy of such praise. Prejudice and folly are for unenlightened people. All are helpless in the face of such beauty; its force is auspicious even to the gods. To sing its praises again with fine words, dance more graciously than the rustling grass or the butterfly with its golden wings spread delicately against the snow, though one may carelessly mistake it for a flower that has fallen from one’s cap. Do not be distracted by young men who flutter their eyebrows. We are all like butterflies in pursuit of the lovely spirit of a young girl. I ran and fell flat on my face, hurting my ankle, but got to my feet again with the aid of a branch, and he figure of a man appeared in the rising mist.

A fearful spirit arose from its ancient abode in the lake, making me sweat terribly, and then its tragic countenance vanished. I was aghast, dumbfounded: such was the terrible power of its beauty, that overwhelmed all who passed by. I saw a pond lined with exquisite pines, and there was Basho’s frog on the bank (11). Someone was jumping in right now, followed by tens of thousands more. The legend had taken its full course, for only a lake with no bottom could hold so many thousands. It was a place famous for its remarkable beauty, unusually celebrated in the common mind. People revere this famous place as the lake without bottom; it is unique in history. There have been countless other bottomless lakes but this is the most beautiful under heaven. In England there is a great swamp that is comparable, and another such place in Germany. The swamp in England is called ‘Shake-sphere’, in Germany Gyoten (12). It is madness to lose yourself in these places. Take heed while you can, and value your independence. We need only look at all the people drowning in this lake to see how deadly it is. It is better to stay away, and so I wrenched myself from my dreams – the dreams of years ago – and awoke.

‘Bunkai meisho: soko shirazu no mizuumi’, in Inagaki Tatsuro, ed. Tsubouchi Shoyo shu, Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1969, pp. 279-82.

Notes

1. A conventional description of the sea which Tsubouchi also uses in the prelude of Shinkyoku Urashima

(1904). According to the legend, a terrifying dragon lived at the bottom of the sea, which suits Tsubouchi’s metaphor in the debate on ‘hidden ideals’ of the dangers of penetrating too deeply a writer’s consciousness.

2. The jittoku (‘ten’ or ‘many’ virtues) was a sleeved garment worn by men in pre-modern times.

3. The Buddhist paradise.

4. A likely reference to another popular haiku by Basho: ‘On a bare branch a crow is perched – autumn evening’.

5. In Buddhism, the soul passes through 84,000 cycles of reincarnation before reaching nirvana.

6. The Bokkai Sea on China’s north-east coastline was traditionally believed to drain all the waters of the world. The third realm in Buddhist cosmology is that of formlessness (above the first of desire and second of form), just prior to nirvana.

7. Traditionally, seven tools are considered necessary for carrying out professional tasks, which nowadays might include such devices as the mobile phone. The 12th century warrior-monk Benkei, a hero of Noh and kabuki drama, is depicted carrying seven tools on his back (the axe, rake, sickle, mallet, saw, staff, and spear).

8. Pines symbolize long life in Japanese culture; the Noh drama Takasago

features paired pine trees that symbolize the harmony and durability of the marital relationship.

9. The temple on Mt Yoshino, near Kyoto, famed for its cherry blossoms.

10. A bridge dating back to the Tang dynasty in the ancient Chinese city of Suzhou.

11. Matsuo Basho (1644-94), ‘an ancient pond – a frog jumps in – the sound of water’. Basho’s ‘frog’ haiku and the 11th century Tale of Genji

are both classic literary works that are mentioned frequently in Tsubouchi’s comparative studies at this time.

12. Shakespeare and Goethe. Gyoten

means ‘astonishment’, the Romantic sense of awe.

③ excerpt from Shingakugekiron

(Theory of Musical Drama) (Waseda University Press, November 1904)

The Necessity of Theatrical Reform

I believe that any discussion of theatrical reform in contemporary Japanese society, whether drama is viewed from the outside as a serious undertaking or as a mere pastime, should regard it as a major priority in the post-war situation (1), and I would like to explain my reasoning in some detail.

First Reason

Any country that calls itself civilized must create for itself a national music and drama. The nation that does not at any one time seek to appeal to the ears and eyes of the majority of its citizens, to soothe and satisfy their hearts through music and drama, while at the same time providing the necessary training and facilities for those arts that entertain the masses and develop their sensitivities, is not a nation at all. Even if such an undeveloped country is not exactly barbarian, it is surely either some terrible tyranny or else a country severely impeded by poverty, and yet this is no different in character from a nation in which it is only the upper classes who indulge in luxuries, serving their personal pleasures alone, while the majority are tied to a life of toil, hunger and hardship. It is through a nation’s music and drama that its moral fiber, customs, and all its various traits and qualities are best appreciated; the sages of the East have always been vocal in their praise for things musical. This, then, is the first reason why music and drama are so important for a country to be deemed civilized.

The five major art forms are conventionally considered to be music, drama, painting, sculpture and poetry, but in terms of its power to please and console the human heart (2), irrespective of social class, education and intelligence, and of its latent capacity to move many people at a single moment, there can be no greater artistic forms than music and drama or rather what we should call musical drama, and which therefore has a most serious role in the development of a civilized nation. There were musical dramas in ancient Greece, as there still are in Europe today. In the Eastern world, musical dramas have been known in China since long ago, and in Japan we have Noh drama, joruri

and kabuki dance drama (furigoto) (3). These all have their own characteristics, and each express national differences: of culture of the ages from which they come, of society, of social degree and quality.

As I have mentioned, there were four great playwrights in ancient Greece, including Euripides and Sophocles, whose dramas had a ceremonial function and are still held in great esteem today, and likewise in Rome there were Seneca, Plautus and Terence; these plays served as entertainment for all classes of society. Modern Europe, since the great cultural revival of the late 16th century known as the Renaissance, has seen the gradual development of a new dramatic form called the opera. It is regrettable that up to now there have been no operatic masterpieces or composers in the East that are comparable to Western countries. These works may be honestly likened to the ceremonial music and drama of a civilized nation, and in so far as they give pleasure to all classes of society as well as foreign guests they serve as a pleasant means of cultivating lofty ideals. Within Oriental drama, for example the drama you see in Shanghai and indeed Peking, which have no historical connection with the ancient Chinese Seisho, Biwa and Jisshukyoku plays, there are similarities with our kabuki drama, although they are not the ceremonial drama of a civilized country. The sounds of the coarser style of Chinese music must sound cacophonous to untrained ears, their melodies bringing only discomfort. It would be difficult indeed for such music to advance our knowledge, entertain foreign guests and so on in the 20th century.

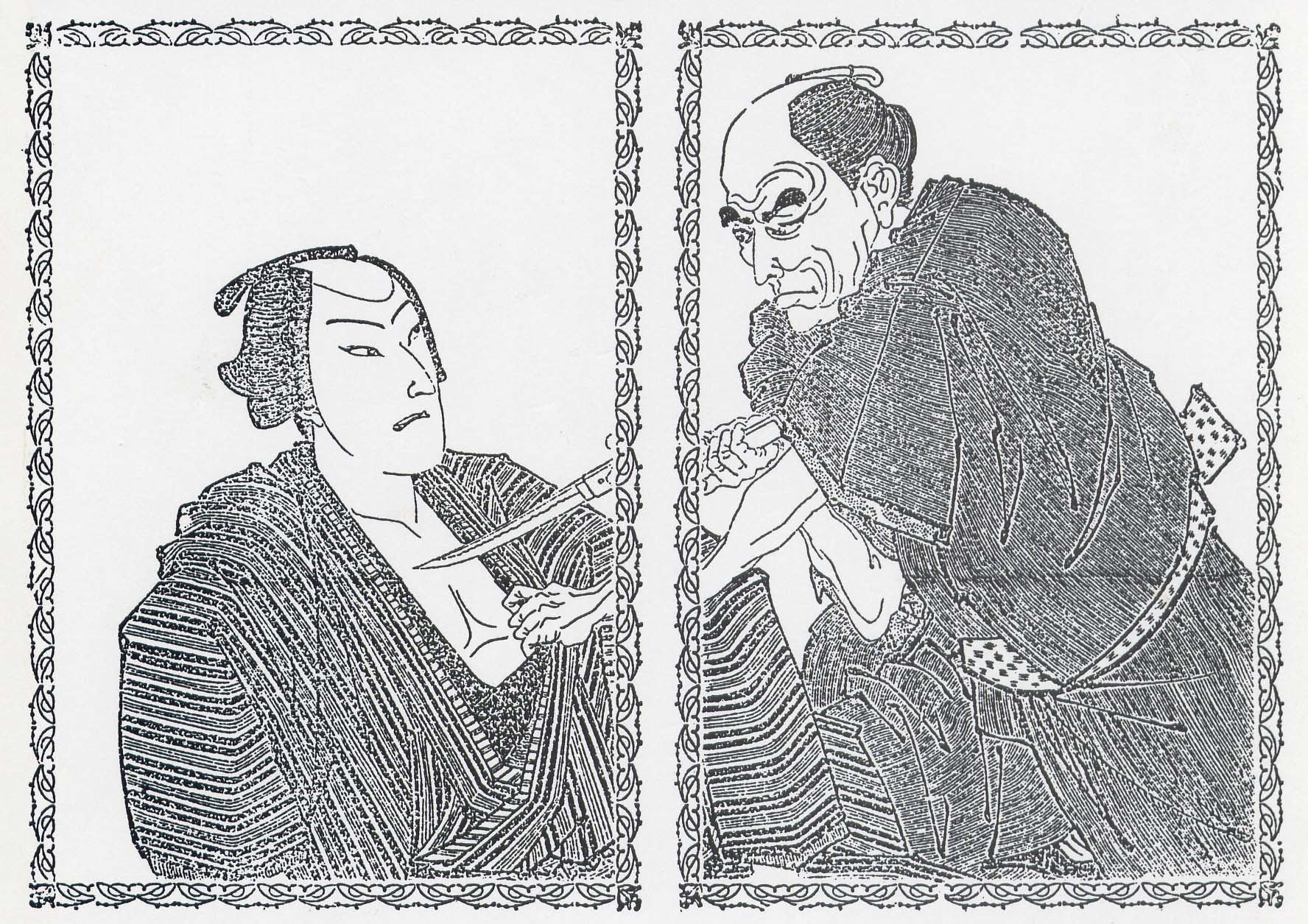

This is not the place, however, for foreign drama, for Japanese musical drama as one would expect is different. Is there any musical drama today that is truly capable of appealing to all classes of society? The Noh is the refined legacy of a former age, or to put it strictly, of the Buddhist spirituality and warrior culture of three hundred years ago, like the treasures of the Shosoin (4), but in a broad sense it is incapable of fulfilling its function of consoling and entertaining the masses of today, of enlightening and instructing them, and of awakening their spirits to the future. For when we consider how these plays are written, their ideas and language, we realize that they are basically for the upper classes and for refined sensibilities, and that they can therefore satisfy only people of such high rank. The frequent efforts made to introduce foreigners to Noh drama show how the genre is regarded as something rare and recherché, like antiques that opening windows onto the past: the jewel in the crown. With its frequent use by government officials to entertain foreign guests, one wonders whether since the basic meaning of hospitality is to delight the invited parties, perhaps Noh drama comes close to this purpose of soothing strained nerves. Likewise, just as the true essence of Noh may be unappreciated by foreign guests, when our own diplomats and officials go to the opera in Germany and Italy they will also hear and see it in a different way. Nevertheless, since the great kabuki actors Danjuro and Kikugoro died in 1903, their successors are unable to perform such classics as Kanjincho

and Momijigari. Japan now ranks among the most powerful nations since its victory against Russia in 1905, but in terms of culture is still undeveloped.

Joruri

and kabuki furigoto

are relatively new in comparison to Noh drama, and therefore easier for ordinary people to comprehend. The Takemoto style of joruri

is widely known among Japanese people, and thus sets a standard for popular entertainment, but quite apart from its status among the people in feudal times, it could never, in terms of its dramatic techniques, its language, the tone of its moral principles, the particular timbre of its shamisen and percussive accompaniments, the vocal modulations of the narrators, the apparel of puppets, and its theatrical gestures and rhetoric, meet the aesthetic demands of the present progressive age. It is more suited in that regard to the refined tastes and specialist knowledge of the upper class. Nowadays, people such as myself enjoy reading the works of Chikamatsu, and Takeda and Miyoshi from the 17th and 18th centuries, as a kind of literature, but when they are staged for us by preeminent katarite

and gidayu

chanters, our initial reaction is usually one of dislike. Certainly as music, the Takemoto style is somewhat vulgar, coarse and wild, and cannot be considered representative of Japanese music in the way that Western masterpieces can of theirs. If someone were to organize a concert for the benefit of foreign visitors, then that person would have to make do with the meager facilities in Ushigome (5) in contrast to the splendid concert halls of Paris. I find it remarkable that even with the passing of Danjuro and Kikugoro, kabuki should still be regarded as some kind of quaint curiosity.

As for furigoto

dance drama, this can be said to reflect the ideas and tastes of Edo culture extending from the early 18th through to the early 19th centuries, or more specifically the Rien and Kyosha demi-monde (6). The formal drama of this era is generally somewhat contrived in taste, with values such as date

(dandyism), kankatsu

(gaudiness), hade

(show), share

(wit), hari

(pluck), ikiji

(confidence), sui

(style), tsu

(expertise), iki

(chic) and shibumi

(elegant simplicity) combining over the hundred or so years of historical refinement to take a shape that is too artificial, too unnatural and too unique (and lacking, of course, the subtle flavours of karasumi

dried mullet roe and of sea urchin) to seem anything but alien to those who have not been educated in those values. One would hope that such things are no longer practiced, but if they still are to some extent, I would say that the people of today can never benefit from a culture based on the abnormal, the peculiar, the deviant and the ethereal. The arts of any country have developed over several hundred years, and so it is expected that on sudden exposure to them for the first time people will struggle to appreciate their aesthetic value, and this is generally all the more the case of furigoto

dance drama, where without adequate instruction much of that value will be lost. For Japanese people from the provinces and elsewhere, who may have seen furigoto

five or six times, or more occasionally, but even if they have seen it ten times, they still may not understand its essential meaning, but because it is an art form based on serious materialistic and worldly ideals, it insinuates the clash of duty and feeling in human behaviour, speaks of universal feelings and desires, above all of erotic love. Rather, all the incidents, characters, prologues, engo

(word play), ideals and fancies cannot be distinguished separately from the traditions of the Rien and Kyosha, but if one were to present it to foreigners, they would enjoy it, and if they were to request a detailed translation, all those sophisticated characters and their parties would turn red with embarrassment. It is said that opera cannot be understood without knowing a little about it, even if the pace is somewhat different. The appreciation of furigoto

demands a critical knowledge of both the style of the early 18th century Yoshiwara courtesans and of the kabuki chronicle plays (7).

As for Japanese music, we have koto, shakuhachi

and gagaku, and in our music academies Western music, although koto

and shakuhachi

are for solo rather than ceremonial performance. Whereas the gagaku

is like the sacred treasures of the Shosoin, Western music has been borrowed from foreign countries, and has yet to acquire Japanese features. These forms will all play an essential role in the future development of Japanese music, and I can only insist that the loss of even just a few of them would be to the detriment of world culture as a whole. In the recent war with Russia, Imperial Japan faced a world power on equal terms, but while our own people are responsive to Western works of literature, we are yet to produce a single work that has moved the hearts of foreigners, and although Japanese art has acquired a semi-antique status in the West, they have absorbed nothing of our ceremonial music or of the ideas that inspire the Japanese music in the 20th century. The tastes of the lower classes are stuck in the vulgar naniwabushi

(which dates back even earlier than the Genroku era) and the parochial Genjibushi(8), while the educated classes prefer the antique tastes formulated by the tea men and anchorites of a hundred, nay three or four hundred years ago, which is somewhat strange for a country like the Japan of today so committed to intellectual advancement. Pictures of the Kawakami theatrical couple have appeared in Western newspapers, and a short biography of the late kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjuro in some encyclopedia alongside the statesmen Okuma Shigenobu and Ito Hirobumi (9), but if one were to assume that Japanese drama has attained a global reputation, that would be a great mistake. One wonders whether Westerners rank Japanese drama on the same level as Chinese drama, or somewhat lagging behind. In any case, whether our drama is known abroad or not, with the deaths of Danjuro and Kikugoro, there can be no hope that it will become better known in its present condition. Indeed, it is as a natural consequence of its frenetic pursuit of the signs of the times that the arts continue to deteriorate, and so if we abandon them in this way, then the skills necessary for revival will be lost, as will the means for preserving the traditional kabuki. This is a fundamental reason for reforming Japanese drama in the post-war era.

Second Reason

It goes without saying that the above is not the only reason. With the eventual conclusion of the war, the Empire now stands on a truly equal footing with other civilized countries, thereby greatly strengthening its exchanges as a nation and among Japanese people. Cultural exchanges have become a lot more frequent, sophisticated and complex, striking new trends have appeared in daily life, and in a few years’ time, as the population grows and the struggle to survive becomes gradually harder, the gap between rich and poor will become more conspicuous, leading to various kinds of frightening response to various kinds of situation and to increasingly louder calls for social equality. Abroad, we hear narrow-minded, illogical arguments about the Yellow Peril, and within Japan a hidden and mysterious current of socialism has been spreading its tentacles through society. Other countries, moreover, are gradually taking fright of our success, and even envying us driven by numerous groundless suspicions. To the countries of the West we exhibit the truth, that is to say the lofty ideals and tastes of our civilization, while within Japan these tastes are circulated at each level of society for the development of human feeling, and in this regard it is essential that Japanese music be made available to all classes and that the arts be used for the purpose of emotional development. We must abandon the idea of matching the experiences of the workaday world in which the man of the house drowns his daily tribulations and his wife her cares in a day at the theatre. In this regard, the problem of entertaining people is an extremely important one, and I think that the tradition in times past of lords and conquerors winning the people’s hearts by creating pleasure gardens for them and holding festivals is highly relevant here. I have previously discussed the essential importance that theatre will have in entertaining Japanese people (10):

When we think of what it gives us on those occasions when we most need to open our mouths and laugh and yet scarcely know how, those days when we are most afflicted by the daily struggle for survival, the provision of entertainments to console us in our sorrows, and to help us forget them at least, is a matter of pressing concern. Yet the single evil of the present age is our excessive self-consciousness. This is a phenomenon which began in Europe at the end of the 18th century and has spread gradually into Japan since around the time of the Meiji Restoration to the present when unless people exercise a little self-denial there can be no telling what will happen. We may wish to lament this state of affairs, to return to the innocence of the past, to scorn the precocious literary styles of our new civilization and to long for the ignorant barbarity of a former age, but this would be like trying to become a child again, suppressing the maturity of adult hindsight; it would be a futile conversation that runs counter to the laws of evolution. Yet the truth is that self-consciousness has raised awareness of human suffering tenfold compared with former times. In contrast to the innocent past, when people knew no better, people of today are so much more meticulous about things as they pursue their goals of self-realization. They cannot forget their domestic matters even for the slightest moment, and because they are always so concerned with what others think of them, they have a lot of worries and complaints, and above all are terrible egoists who cannot rest themselves for a single moment, being preoccupied by the hungry ghost of material gain. They are angry, unhappy, envious and pusillanimous, terrified of being found out. It is not only that too much self-consciousness disturbs people’s peace and makes them more aware of their sufferings but that it warps people’s natural magnanimity, it degrades them, and makes them unworthy.

Third Reason

The word ‘entertainment’ is somewhat misleading, but I cannot think of a better one. If we understand the word to be more spiritual than sensual, then it is hardly any different from saying that the function of literary art is entertainment, and if we consider that literature’s main function is broadly similar to religion, what seems to me most deeply striking is that for all the various historical, cultural and systematic differences that account for the subtle mysteries of the human heart, literature is fundamentally unchanging. Literature reminds us that human beings are basically alike in their passing fads and aesthetic ideals; it moves people’s hearts, brings them together and influences them for the common good, enables them to appreciate the feelings of people of long ago and the people of other countries whom we regard as our enemies as individual human beings, to embrace people throughout all four corners of the world as brothers. This is what art and literature, along with religion, do well, and is what our statesmen, educationists and moralists struggle to do with some difficulty, and since literature is not confined to teaching dogma and the ancestral rites found in religion, it should be more effective than religion, but its actual power is weak and indistinct.

Apart of course from a few inspired works, the best to which the average work of literature can aspire is no more than fantasy. The majority do not attain to what I cite as this third factor, the capacity of literature for perfection. Yet the issue of how it would be best to reform our national drama remains the pressing problem, and on which I would like to offer a few observations.

A Strategy for Reforming Our National Drama

What I would like to propose is nothing particularly radical, and indeed have no doubt made similar proposals before, or else they are already shared by the majority of educated people. My reason for repeating these proposals as though for the first time is simply my desire to effect a strategy for reforming our national drama, and so by making myself clear in this way hope to gain the widest possible support for my views.

Any strategy that is to have a lasting impact on the nation, and indeed the world, will be of no benefit if it sticks to existing procedures, makes only temporary concessions, imports novelty for the sake of novelty irrespective of its suitability to native conditions, and adopts an irrational eclecticism that kills both beauty and individual characteristics; such a strategy, in my view, can have only harmful effects. Of course, there is absolutely no harm in experimentation as a supplementary measure, but if anyone supposes that they can achieve reform through relying on such experiments, they are sorely mistaken.

This is surely because the peculiar features of a national culture, at all stages of its development, have evolved over several hundred years of learning and cultivation. These characteristics, whether political, religious, literary or artistic, must inevitably differ in nature from those of other countries, and because they have been passed down undiluted over several hundred years, have had effects that are utterly unknown in foreign countries. Yet because the influence of foreign competition has been over a rather shorter time, a culture’s particular features may appear debased and moribund, indeed almost completely moribund and in need of reform. They are not yet completely dead, however, and it is unwise and short-sighted to uproot and discard them, in which case the proper thing is to leave the roots, or in some other way preserve them. It seems there are some critics who would rather let such old trees wither and decay and impatiently rush to plant new trees imported from abroad. Of course, if these transplants are adapted to our climate, and produce flowers and fruit, that is all well and good, but I suspect that without adequate care nine out of ten will not, and that even with adequate care, they will take a century at least to become acclimatized, and that few will flourish beyond their roots. This is a situation that calls for discretion.

I would argue that since it is not easy to cultivate foreign seeds, it is preferable to care for and nurture our old trees first without cutting them down, and that there are two approaches to doing so. One is to prepare for change, and the other is more rigidly conservative. The first is the research-based approach we have been adopting up to now; the second to reject notions such as progress and competition out of hand and to cling rigidly to the past, simply because that is what is already in place. This latter approach represents a somewhat negative view of things, and is probably not the one we should take. Yet whatever the case, I believe that lasting reform, for the sake of the country and for humanity, must be based on the unique features of our culture as they have been cultivated and inculcated over many hundreds of years. This is the principle on which any true civilization is founded: through consolidation and refinement of each culture’s uniquely beautiful characteristics. In pursuing reform, imitation is no more than repeating someone else’s idea and should be avoided at all costs, while eclecticism destroys a culture’s unique characteristics. If we are to reform our national drama, it is natural therefore that we should seek to build on and improve its unique features.

Outline of Reform

In retrospect, it is no exaggeration to suggest that the age of the Noh was the first age of the musical drama, the eras of Genroku and Kyoho in which the Takemoto joruri

came to being the second age (11), and the current fourth decade of Meiji the third era. The Noh’s founders both comprehended and assimilated the various auditory and visual elements of their age that comprise the musicality and theatricality of their drama. Likewise, Chikamatsu and Takemoto in the Genroku era assimilated all that appealed to the eyes and ears of their contemporaries to create the remarkable phenomenon that is Takemoto joruri. In this regard, although they had a considerable advantage over the Noh and moreover their debt to Chinese drama was not small, their basic method was no different in seeking to rationalize the extant national drama, and if that is the case then in the present Meiji era we must learn from the history of musical drama as we set about developing its future. This is not only a matter of assimilating the most advanced elements of Japanese musical drama within a new genre, but I believe of fostering a method for distilling the essence of our national drama that will respond with enthusiasm to past traditions just as it refers to the more recent introduction of Western forms. Among these, it is the furigoto

dance drama that I regard as taking pride of place in our national drama.

The point of which we should be particularly aware are the fundamental differences between so-called Western opera and our native musical drama. Western opera also has its writers and artists, but they are quite different from our own; to be more precise, Japanese musical drama is based on the dance, but that of the West on sung lyric. This is why opera as it exists in its present state can never be performed in Japan for at least another hundred years. Indeed, it is quite absurd from the point of view of the essence of sung lyric and of our native artists and musical instruments even to conceive of a Japanese opera: almost entirely impossible. Even if it were possible, as I have argued, it would be like infusing the glorious peony of a great Western tradition with some tedious concoction, and from the viewpoint of contributing to world civilization would have hardly any effect at all. I cannot tell what will happen in another hundred or two hundred years, but for the time being have no doubt that in the present circumstance we should concentrate our efforts on creating a new native dramatic genre based on furigoto.

As regards the furigoto, it seems that no one has yet to provide a satisfactory exposition of its qualities, but I feel that as an art form that has in actual fact passed through its own particular process of change, development and purification, it already contains some unique features in the context of world culture; indeed, it is ‘unique’. In ancient Rome it seems that there was something like the furigoto, but now no trace of it remains. There are the ballet and the pantomime in the West but from what I can gather from my inquiries, it seems that these too are quite different in character from furigoto. Even were we to accomplish our goals of reform, building on them through the decades ahead, and still find ourselves unable to create a national drama based on furigoto

that rivalled the song-based musical drama of the West, our drama would still be remarkably unique in the world, and would be priced even many more times than is Japanese painting now regarded by the cognoscenti of the West.

People who discuss the reform of Japanese drama mention the improvement of script writing, the challenge of Western instrumentation and adoption of Western-style harmonies as urgent necessities but none of these are absolute, and if I may say so, are minor stopgap measures. This is to say we cannot put too much emphasis on minor reforms, but should look instead to the more presentable of our native genres, such as nagauta, supplementing their vitality and elegance with the graver sonorities of yokyoku

and icchu. Styles such as tokiwazu, tomimoto

and takemoto

provide a useful dramatic point of reference that can be enhanced by kiyomoto

and so on, while the various kinds of Western music impart a grand, heroic quality (12). Reform of our national drama must always seek to develop and refine its unique characteristics among which the furigoto

is central.

I think I have made my point quite rigorously enough, and will be delighted if others share my sentiments. There may be some who doubt the importance of theatrical reform, but for me it is a matter of the highest importance in the post-war era.

Shingakugekiron

(extract), in Inagaki Tatsuro, ed. Tsubouchi Shoyo shu, Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1969, pp. 344-52

Notes

1. The Russo-Japanese War was fought between 1904 and 1905.

2. In his writings, Tsubouchi frequently uses this conventional image of art as ‘consolation’.

3. Furigoto

(or shosagoto) is a type of kabuki dance drama performed either as part of a play or as a set piece, usually by a solo onnagata (female impersonator), and as a genre that emphasizes the beauty of the dance and costumes and the actor’s skill, Tsubouchi’s underlying aesthetic comparison is with the virtuosity of operatic aria.

4. The treasure house, constructed in the 8th century, of Todaiji temple in Nara.

5. The reference is to an early modern concert hall built in Ushigome in downtown Tokyo in the Meiji era.

6. A Tang dynasty emperor taught music and playwriting in his pear garden (rien), and this name was adapted in the Edo era as a name for the kabuki world of performers and connoisseurs. Kyosha were ‘street knights’, armed ruffians who protected the weak, whose samurai mores became a model for the manly aragoto

style of acting in Edo kabuki.

7. Tsubouchi is arguing that modern Japanese culture should be capable of bringing traditional styles such as furigoto

to a mass public without having to reproduce the elitist hierarchies in which those styles were originally cultivated.

8. Traditional genres in which sentimental ballads are sung to shamisen accompaniment.

9. Tsubouchi is conscious of Japan’s image in contemporary Western publications. Actor Kawakami Otojiro (1864-1911) made two sensational tours of the United States and Europe with his wife the actress and former geisha Sada Yacco (1871-1946) between 1899 and 1902. Kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjuro IX had died in 1903. Statesman Okuma Shigenobu (1838-1922) was the founder of Waseda University and twice prime minister of Japan. Ito Hirobumi (1841-1909) served four times as prime minister before his assassination by a Korean nationalist.

10. As a journalist as well as scholar, Tsubouchi frequently recycled his arguments.

11. Two relatively lengthy imperial eras in early modern Japanese history in which the economy prospered and the arts flourished: the Genroku era between 1688 and 1704 and Kyoho from 1716 to 1736.

12. In his musical and choreographic directions for Shinkyoku Urashima

(1904), Tsubouchi imitates the scope of Wagnerian opera by requesting each of the traditional styles listed here, as well as Western music at the end. In imitation of the tonal range of Wagner's scores, the traditional styles Tsubouchi encompass a range of timbres, nagauta

lyrical and melodic, tokiwazu

intense and 'masculine', kiyomoto

more 'feminine', and so on.